BEING AN ACCOUNT OF

HIS CAREER

AND ADVENTURES ON THE COAST,

IN THE INTERIOR, ON SHIPBOARD, AND IN

THE WEST INDIES.

WRITTEN OUT AND EDITED FROM THE

Captain’s Journals, Memoranda and Conversations,

BY

NEW YORK:

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY,

846 & 848 BROADWAY.

LONDON: 16 LITTLE BRITAIN.

M.DCCC.LIV.

MANDINGO CHIEF AND HIS SWORD BEARER.

MANDINGO CHIEF AND HIS SWORD BEARER. Entered,

according to Act of Congress, in the year 1854, by

BRANTZ MAYER,

in the Clerk’s Office of the United States District Court for the District of

Maryland.

TO

N. P. WILLIS,

OF IDLEWILD.

My Dear Willis,

While inscribing this work with your name, as a testimonial of our long, unbroken friendship, you will let me say, I am sure, not only how, but why I have written it.

About a year ago I was introduced to its hero, by Dr. James Hall, the distinguished founder and first governor of our colony at Cape Palmas. While busy with his noble task in Africa, Dr. Hall accidentally became acquainted with Captain Canot, during his residence at Cape Mount, and was greatly impressed in his favor by the accounts of all who knew him. Indeed,—setting aside his career as a slaver,—Dr. Hall’s observation convinced him that Canot was a man of unquestionable integrity. The zeal, moreover, with which he embraced the first opportunity, after his downfall, to mend his fortunes by honorable industry in South America, entitled him to respectful confidence. As their acquaintance ripened, my friend gradually drew from the wanderer the story of his adventurous life, and so striking were its incidents, so true its delineations of African character, [Pg iv] that he advised the captain to prepare a copious memorandum, which I should write out for the public.

Let me tell you why I undertook this task; but first, let me assure you that, entertaining as the story might have been for a large class of readers, I would not have composed a line for the mere gratification of scandalous curiosity. My conversations with Canot satisfied me that his disclosures were more thoroughly candid than those of any one who has hitherto related his connection with the traffic. I thought that the evidence of one who, for twenty years, played the chief part in such a drama, was of value to society, which, is making up its mind, not only about a great political and domestic problem, but as to the nature of the race itself. I thought that a true picture of aboriginal Africa,—unstirred by progress,—unmodified by reflected civilization,—full of the barbarism that blood and tradition have handed down from the beginning, and embalmed in its prejudices, like the corpses of Egypt,—could not fail to be of incalculable importance to philanthropists who regard no people as beyond the reach of enlightenment.

The completed task rises before me like a moving panorama whose scenery and background are the ocean and tropics, and whose principal actor combines the astuteness of Fouché with the dexterity of Gil Blas. I have endeavored to set forth his story as plainly as possible, letting events instead of descriptions develope a chequered life which was incessantly connected with desperate men of both colors. As he unmasked his whole career, and gave me leave to use the incidents, I have not dared to hide what the actor himself displayed no wish to conceal. Besides the sketches of character which familiarize us with the aboriginal negro in Africa, there is a good moral in the resultless life, which, after all its toils, hazards, and successes leaves the adventurer a stranded wreck in the prime of [Pg v] manhood. One half the natural capacity, employed industriously in lawful commerce, would have made the captain comfortable and independent. Nor is there much to attract in the singular abnegation of civilized happiness in a slaver’s career. We may not be surprised, that such an animal as Da Souza, who is portrayed in these pages, should revel in the sensualities of Dahomey; but we must wonder at the passive endurance that could chain a superior order of man, like Don Pedro Blanco, for fifteen unbroken years, to his pestilential hermitage, till the avaricious anchorite went forth from the marshes of Gallinas, laden with gold. I do not think this story is likely to seduce or educate a race of slavers!

The frankness of Canot’s disclosures may surprise the more reserved and timid classes of society; but I am of opinion that there is an ethnographic value in the account of his visit to the Mandingoes and Fullahs, and especially in his narrative of the wars, jugglery, cruelty, superstition, and crime, by which one sixth of Africa subjects the remaining five sixths to servitude.

As the reader peruses these characteristic anecdotes, he will ask himself how,—in the progress of mankind,—such a people is to be approached and dealt with? Will the Mahometanism of the North which is winning its way southward, and infusing itself among the crowds of central Africa, so as, in some degree, to modify their barbarism, prepare the primitive tribes to receive a civilization and faith which are as true as they are divine? Will our colonial fringe spread its fibres from the coast to the interior, and, like veins of refreshing blood, pour new currents into the mummy’s heart? Is there hope for a nation which, in three thousand years, has hardly turned in its sleep? The identical types of race, servitude, occupation, and character that are now extant in Africa, may be found on the Egyptian monuments built forty centuries ago; while a Latin poem, attributed to [Pg vi] Virgil, describes a menial negress who might unquestionably pass for a slave of our Southern plantations:

It will be seen from these hints that our memoir has nothing to do with slavery as a North American institution, except so far as it is an inheritance from the system it describes; yet, in proportion as the details exhibit an innate or acquired inferiority of the negro race in its own land, they must appeal to every generous heart in behalf of the benighted continent.

It has lately become common to assert that Providence permits an exodus through slavery, in order that the liberated negro may in time return, and, with foreign acquirements, become the pioneer of African civilization. It is attempted to reconcile us to this “good from evil,” by stopping inquiry with the “inscrutability of God’s ways!” But we should not suffer ourselves to be deceived by such imaginary irreverence; for, in God’s ways, there is nothing less inscrutable than his law of right. That law is never qualified in this world. It moves with the irresistible certainty of organized nature, and, while it makes man free, in order that his responsibility may be unquestionable, it leaves mercy, even, for the judgment hereafter. Such a system of divine law can never palliate the African slave trade, and, in fact, it is the basis of that human legislation which converts the slaver into a pirate, and awards him a felon’s doom.

For these reasons, we should discountenance schemes like those proposed not long ago in England, and sanctioned by the [Pg vii] British government, for the encouragement of spontaneous emigration from Africa under the charge of contractors. The plan was viewed with fear by the colonial authorities, and President Roberts at once issued a proclamation to guard the natives. No one, I think, will read this book without a conviction that the idea of voluntary expatriation has not dawned on the African mind, and, consequently, what might begin in laudable philanthropy would be likely to end in practical servitude.

Intercourse, trade, and colonization, in slow but steadfast growth, are the providences intrusted to us for the noble task of civilization. They who are practically acquainted with the colored race of our country, have long believed that gradual colonization was the only remedy for Africa as well as America. The repugnance of the free blacks to emigration from our shores has produced a tardy movement, and thus the African population has been thrown back grain by grain, and not wave by wave. Every one conversant with the state of our colonies, knows how beneficial this languid accretion has been. It moved many of the most enterprising, thrifty, and independent. It established a social nucleus from the best classes of American colored people. Like human growth, it allowed the frame to mature in muscular solidity. It gave immigrants time to test the climate; to learn the habit of government in states as well as in families; to acquire the bearing of freemen; to abandon their imitation of the whites among whom they had lived; and thus, by degrees, to consolidate a social and political system which may expand into independent and lasting nationality. Instead, therefore, of lamenting the slowness with which the colonies have reached their vigorous promise, we should consider it a blessing that the vicious did not rush forth in turbulent crowds with the worthy, and impede the movements of better folks, who were still unused to the task of self-reliance.

[Pg viii] Men are often too much in a hurry to do good, and mar by excessive zeal what patience would complete. “Deus quies quia æternus,” saith St. Augustine. The cypress is a thousand years in growth, yet its limbs touch not the clouds, save on a mountain top. Shall the regeneration of a continent be quicker than its ripening? That would be miracle—not progress.

Accept this offering, my dear Willis, as a token of that sincere regard, which, during an intimacy of a quarter of a century, has never wavered in its friendly trust.

Faithfully, yours,

Brantz Mayer.

Baltimore, 1st July, 1854.

[1] Moretum,—Carm. Virg. Wagner’s ed. vol. 4, p. 301.

| PAGE | |

| CHAP. I.—My parentage and education—Apprenticed at Leghorn to an American captain—First voyage—its mishaps—overboard—black cook—Sumatra—cabin-boy—Arrival in Boston—My first command—View of Boston harbor from the mast-head—My first interview with a Boston merchant, William Gray | 1 |

| CHAP. II.—My uncle tells my adventure with Lord Byron—Captain Towne, and my life in Salem—My skill in Latin—Five years voyaging from Salem—I rescue a Malay girl at Quallahbattoo—The first slave I ever saw—End of my apprenticeship—My backslidings in Antwerp and Paris—Ship on a British vessel for Brazil—The captain and his wife—Love, grog, and grumbling—A scene in the harbor of Rio—Matrimonial happiness—Voyage to Europe—Wreck and loss on the coast near Ostend | 10 |

| CHAP. III.—I design going to South America—A Dutch galliot for Havana—Male and female captain—Run foul of in the Bay of Biscay—Put into Ferrol, in Spain—I am appropriated by a new mother, grandmother, and sisters—A comic scene—How I got out of the scrape—Set sail for Havana—Jealousy of the captain—Deprived of my post—Restored—Refuse to do duty—Its sad consequences—Wrecked on a reef near Cuba—Fisherman-wreckers—Offer to land cargo—Make a bargain with our salvors—A sad denouement—A night bath and escape | 19 |

| CHAP. IV.—Bury my body in the sand to escape the insects—Night of horror—Refuge on a tree—Scented by bloodhounds—March to the rancho—My guard—Argument about my fate—“My Uncle” Rafael suddenly appears on the scene—Magic change effected by my relationship—Clothed, and fed, and comforted—I find an uncle, and am protected—Mesclet—Made cook’s mate—Gallego, the cook—His appearance and character—Don Rafael’s story—“Circumstances”—His counsel for my conduct on the island | 31 |

| CHAP. V.—Life on a sand key—Pirates and wreckers—Their difference—Our galliot destroyed—the gang goes to Cuba—I am left with Gallego—His daily fishing and nightly flitting—I watch him—My discoveries in the graveyard—Return of the wreckers—“Amphibious Jews”—Visit from a Cuban inspector—“Fishing license”—Gang goes to Cape Verde—Report of a fresh wreck—Chance of escape—Arrival—Return of wreckers—Bachicha and his clipper—Death of Mesclet—My adventures in a privateer—My restoration to the key—Gallego’s charges—His trial and fate | 41 |

| [Pg x] CHAP. VI.—I am sent from the key—Consigned to a grocer at Regla—Cibo—His household—Fish-loving padre—Our dinners and studies—Rafael’s fate—Havana—A slaver—I sail for Africa—The Areostatico’s voyage, crew, gale—Mutiny—How I meet it alone—My first night in Africa! | 57 |

| CHAP. VII.—Reflections on my conduct and character—Morning after the mutiny—Burial of the dead—My wounds—Jack Ormond or the “Mongo John”—My physician and his prescription—Value of woman’s milk—I make the vessel ready for her slave cargo—I dine with Mongo John—His harem—Frolic in it—Duplicity of my captain—I take service with Ormond as his clerk—I pack the human cargo of the Areostatico—Farewell to my English cabin-boy—His story | 68 |

| CHAP. VIII.—I take possession of my new quarters—My household and its fittings—History of Mr. Ormond—How he got his rights in Africa—I take a survey of his property and of my duties—The Cerberus of his harem—Unga-golah’s stealing—Her rage at my opposition—A night visit at my quarters—Esther, the quarteroon—A warning and a sentimental scene—Account of an African factor’s harem—Mongo John in his decline—His women—Their flirtations—Battles among the girls—How African beaus fight a duel for love!—Scene of passionate jealousy among the women | 76 |

| CHAP. IX.—Pains and dreariness of the “wet season”—African rain!—A Caravan announced as coming to the Coast—Forest paths and trails in Africa—How we arrange to catch a caravan—“Barkers,” who they are—Ahmah-de-Bellah, son of the Ali-Mami of Footha-Yallon—A Fullah chief leads the caravan of 700 persons—Arrival of the caravan—Its character and reception—Its produce taken charge of—People billeted—Mode of trading for the produce of a caravan—(Note: Account of the produce, its value and results)—Mode of purchasing the produce—Sale over—Gift of an ostrich—Its value in guns—Bungee or “dash”—Ahmah-de-Bellah—How he got up his caravan—Blocks the forest paths—Convoy duties—Value and use of blocking the forest paths—Collecting debts, &c.—My talks with Ahmah—his instructions and sermons on Islamism—My geographical disquisitions, rotundity of the world, the Koran—I consent to turn, minus the baptism!—Ahmah’s attempt to vow me to Islamism—Fullah punishments—Slave wars—Piety and profit—Ahmah and I exchange gifts—A double-barrelled gun for a Koran—I promise to visit the Fullah country | 84 |

| CHAP. X.—Mode of purchasing Slaves at factories—Tricks of jockeys—Gunpowder and lemon-juice—I become absolute manager of the stores—Reconciliation with Unga-golah—La belle Esther—I get the African fever—My nurses—Cured by sweating and bitters—Ague—Showerbath remedy—Mr. Edward Joseph—My union with him—I quit the Mongo, and take up my quarters with the Londoner | 94 |

| CHAP. XI.—An epoch in my life in 1827—A vessel arrives consigned to me for slaves—La Fortuna—How I managed to sell my cigars and get a cargo, though I had no factory—My first shipment—(Note on the cost and profit of a slave voyage)—How slaves are selected for various markets, and shipped—Go on board naked—hearty feed before embarkation—Stowage—Messes—Mode of eating—Grace—Men and women separated—Attention to health, cleanliness, ventilation—Singing and amusements—Daily purification of the vessel—Night, order and silence preserved by negro constables—Use and disuse of handcuffs—Brazilian slavers—(Note on condition of slavers since the treaty with Spain) | 99 |

| CHAP. XII.—How a cargo of slaves is landed in Cuba—Detection avoided—“Gratificaciones.” Clothes distributed—Vessel burnt or sent in as a coaster, or in distress—A[Pg xi] slave’s first glimpse of a Cuban plantation—Delight with food and dress—Oddity of beasts of burden and vehicles—A slave’s first interview with a negro postilion—the postilion’s sermon in favor of slavery—Dealings with the anchorites—How tobacco smoke blinds public functionaries—My popularity on the Rio Pongo—Ormond’s enmity to me | 107 |

| CHAP. XIII.—I become intimate with “Country princes” and receive their presents—Royal marriages—Insulting to refuse a proffered wife—I am pressed to wed a princess and my diplomacy to escape the sable noose—My partner agrees to marry the princess—The ceremonial of wooing and wedding in African high life—Coomba | 110 |

| CHAP. XIV.—Joseph, my partner, has to fly from Africa—How I save our property—My visit to the Bagers—their primitive mode of life—Habits—Honesty—I find my property unguarded and safe—My welcome in the village—Gift of a goat—Supper—Sleep—A narrow escape in the surf on the coast—the skill of Kroomen | 118 |

| CHAP. XV.—I study the institution of Slavery in Africa—Man becomes a “legal tender,” or the coin of Africa—Slave wars, how they are directly promoted by the peculiar adaptation of the trade of the great commercial nations—Slavery an immemorial institution in Africa—How and why it will always be retained—Who are made home slaves—Jockeys and brokers—Five sixths of Africa in domestic bondage | 126 |

| CHAP. XVI.—Caravan announced—Mami-de-Yong, from Footha-Yallon, uncle of Ahmah-de-Bellah—My ceremonious reception—My preparations for the chief—Coffee—his school and teaching—Narrative of his trip to Timbuctoo—Queer black-board map—prolix story teller—Timbuctoo and its trade—Slavery | 129 |

| CHAP. XVII.—I set forth on my journey to Timbo, to see the father of Ahmah-de-Bellah—My caravan and its mode of travel—My Mussulman passport—Forest roads—Arrive at Kya among the Mandingoes—My lodgings—Ibrahim Ali—Our supper and “bitters”—A scene of piety, love and liquor—Next morning’s headache—Ali-Ninpha begs leave to halt for a day—I manage our Fullah guide—My fever—Homœopathic dose of Islamism from the Koran—My cure—Afternoon | 136 |

| CHAP. XVIII.—A ride on horseback—Its exhilaration in the forest—Visit to the Devil’s Fountain—Tricks of an echo and sulphur water—Ibrahim and I discourse learnedly upon the ethics of fluids—My respect for national peculiarities—Our host’s liberality—Mandingo etiquette at the departure of a guest—A valuable gift from Ibrahim and its delicate bestowal—My offering in return—Tobacco and brandy | 143 |

| CHAP. XIX.—A night bivouac in the forest—Hammock swung between trees—A surprise and capture—What we do with the fugitive slaves—A Mandingo upstart and his “town”—Inhospitality—He insults my Fullah leader—A quarrel—The Mandingo is seized and his townsfolk driven out—We tarry for Ali-Ninpha—He returns and tries his countrymen—Punishment—Mode of inculcating the social virtues among these interior tribes—We cross the Sanghu on an impromptu bridge—Game—Forest food—Vegetables—A “Witch’s cauldron” of reptiles for the negroes | 147 |

| CHAP. XX.—Spread of Mahometanism in the interior of Africa—The external aspect of nature in Africa—Prolific land—Indolence a law of the physical constitution—My caravan’s progress—The Ali-Mami’s protection, its value—Forest scenery—Woods, open plains, barrancas and ravines—Their intense heat—Prairies—Swordgrass—River scenery, magnificence of the shores, foliage, flowers, fruits and birds; picturesque towns, villages and herds—Mountain scenery, view, at morning, over the lowlands—An African noon | 153 |

| [Pg xii] CHAP. XXI.—We approach Tamisso—Our halt at a brook—bathing, beautifying, and adornment of the women—Message and welcome from Mohamedoo, by his son, with a gift of food—Our musical escort and procession to the city—My horse is led by a buffoon of the court, who takes care of my face—Curiosity of the townsfolk to see the white Mongo—I pass on hastily to the Palace of Mohamedoo—What an African palace and its furniture is—Mohamedoo’s appearance, greeting and dissatisfaction—I make my present and clear up the clouds—I determine to bathe—How the girls watch me—Their commentaries on my skin and complexion—Negro curiosity—A bath scene—Appearance of Tamisso, and my entertainment there | 157 |

| CHAP. XXII.—Improved character of country and population as we advance to the interior—We approach Jallica—Notice to Suphiana—A halt for refreshment and ablutions—Ali-Ninpha’s early home here—A great man in Soolimana—Sound of the war-drum at a distance—Our welcome—Entrance to the town—My party, with the Fullah, is barred out—We are rescued—Grand ceremonial procession and reception, lasting two hours—I am, at last, presented to Suphiana—My entertainment in Jallica—A concert—Musical instruments—Madoo, the ayah—I reward her dancing and singing | 162 |

| CHAP. XXIII.—Our caravan proceeds towards Timbo—Met and welcomed in advance, on a lofty table land, by Ahmah-de-Bellah—Psalm of joy song by the Fullahs for our safety—We reach Timbo before day—A house has been specially built and furnished for me—Minute care for my taste and comforts—Ahmah-de-Bellah a trump—A fancy dressing-gown and ruffled shirt—I bathe, dress, and am presented to the Ali-Mami—His inquisitive but cordial reception and recommendation—Portrait of a Fullah king—A breakfast with his wife—My formal reception by the Chiefs of Timbo and Sulimani-Ali—The ceremonial—Ahmah’s speech as to my purposes—Promise of hospitality—My gifts—I design purchasing slaves—scrutiny of the presents—Cantharides—Abdulmomen-Ali, a prince and book-man—His edifying discourse on Islamism—My submission | 167 |

| CHAP. XXIV.—Site of Timbo and the surrounding country—A ride with the princes—A modest custom of the Fullahs in passing streams—Visit to villages—The inhabitants fly, fearing we are on a slave scout—Appearance of the cultivated lands, gardens, near Findo and Furo—Every body shuns me—A walk through Timbo—A secret expedition—I watch the girls and matrons as they go to the stream to draw water—Their figures, limbs, dress—A splendid headdress—The people of Timbo, their character, occupation, industry, reading—I announce my approaching departure—Slave forays to supply me—A capture of forty-five by Sulimani-Ali—The personal dread of me increases—Abdulmomen and Ahmah-de-Bellah continue their slave hunts by day, and their pious discourses on Islamism by night—I depart—The farewell gifts—two pretty damsels | 176 |

| CHAP. XXV.—My home journey—We reach home with a caravan near a thousand strong—Kambia in order—Mami-de-Yong and my clerk—The story and fate of the Ali-Mami’s daughter Beeljie | 183 |

| CHAP. XXVI.—Arrival of a French slaver, La Perouse, Captain Brulôt—Ormond and I breakfast on board—Its sequel—We are made prisoners and put in irons—Short mode of collecting an old debt on the coast of Africa—The Frenchman gets possession of our slaves—Arrival of a Spanish slaver | 190 |

| CHAP. XXVII.—Ormond communicates with the Spaniard, and arranges for our rescue—La Esperanza—Brulôt gives in—How we fine him two hundred and fifty doubloons for the expense of his suit, and teach him the danger of playing tricks upon African factors | 196 |

| [Pg xiii] CHAP. XXVIII.—Capt. Escudero of the Esperanza dies—I resolve to take his place in command and visit Cuba—Arrival of a Danish slaver—Quarrel and battle between the crews of my Spaniard and the Dane—The Dane attempts to punish me through the duplicity of Ormond—I bribe a servant and discover the trick—My conversation with Ormond—We agree to circumvent the enemy—How I get a cargo without cash | 200 |

| CHAP. XXIX.—Off to sea—A calm—A British man-of-war—Boat attack—Reinforcement—A battle—A catastrophe—A prisoner | 206 |

| CHAP. XXX.—I am sent on board the corvette—My reception—A dangerous predicament—The Captain and surgeon make me comfortable for the night—Extraordinary conveniences for escape, of which I take the liberty to avail myself | 214 |

| CHAP. XXXI.—I drift away in a boat with my servant—Our adventures till we land in the Isles de Loss—My illness and recovery—I return to the Rio Pongo—I am received on board a French slaver—Invitation to dinner—Monkey soup and its consequences | 218 |

| CHAP. XXXII.—My greeting in Kambia—The Feliz from Matanzas—Negotiations for her cargo—Ormond attempts to poison me—Ormond’s suicide—His burial according to African customs | 222 |

| CHAP. XXXIII.—A visit to the Matacan river in quest of slaves—My reception by the king—His appearance—Scramble for my gifts—How slaves are sometimes trapped on a hasty hunt—I visit the Matacan Wizard; his cave, leopard, blind boy—Deceptions and jugglery—Fetiches—A scale of African intellect | 227 |

| CHAP. XXXIV.—What became of the Esperanza’s officers and crew—The destruction of my factory at Kambia by fire—I lose all but my slaves—the incendiary detected—Who instigated the deed—Ormond’s relatives—Death of Esther—I go to sea in a schooner from Sierra Leone—How I acquire a cargo of slaves in the Rio Nunez without money | 233 |

| CHAP. XXXV.—I escape capture—Symptoms of mutiny and detection of the plot—How we put it down | 240 |

| CHAP. XXXVI.—A “white squall”—I land my cargo near St. Jago de Cuba—Trip to Havana on horseback—My consignees and their prompt arrangements—success of my voyage—Interference of the French Consul—I am nearly arrested—How things were managed, of old, in Cuba | 244 |

| CHAP. XXXVII.—A long holiday—I am wrecked on a key—My rescue by salvors—New Providence—I ship on the San Pablo, from St. Thomas’s, as sailing master—Her captain and his arrangements—Encounter a transport—Benefit of the small-pox—Mozambique Channel—Take cargo near Quillimane—How we managed to get slaves—Illness of our captain—The small-pox breaks out on our brig—Its fatality | 248 |

| CHAP. XXXVIII.—Our captain longs for calomel, and how I get it from a Scotchman—Our captain’s last will and testament—We are chased by a British cruiser—How we out-manœvred and crippled her—Death of our captain—Cargo landed and the San Pablo burnt | 255 |

| CHAP. XXXIX.—My returns from the voyage $12,000, and how I apply them—A custom-house encounter which loses me La Conchita and my money—I get command of a slaver for Ayudah—La Estrella—I consign her to the notorious Da Souza or Cha-cha—His history and mode of life in Africa—His gambling houses and women—I keep aloof from his temptations, and contrive to get my cargo in two months | 260 |

| [Pg xiv] CHAP. XL.—All Africans believe in divinities or powers of various degree, except the Bagers—Iguanas worshipped in Ayudah—Invitation to witness the HUMAN SACRIFICES at the court of Dahomey—How they travel to Abomey—The King, his court, amazons, style of life, and brutal festivities—Superstitious rights at Lagos—The Juju hunts by night for the virgin to be sacrificed—Gree-gree bush—The sacrifice—African priest and kingcraft | 265 |

| CHAP. XLI.—My voyage home in the Estrella—A revolt of the slaves during a squall, and how we were obliged to suppress it—Use of pistols and hot water | 272 |

| CHAP. XLII.—Smallpox and a necessary murder—Bad luck every where—A chase and a narrow escape | 276 |

| CHAP. XLIII.—The Aguila de Oro, a Chesapeake clipper—my race with the Montesquieu—I enter the river Salum to trade for slaves—I am threatened, then arrested, and my clipper seized by French man-of-war’s men—Inexplicable mystery—We are imprisoned at Goree—Transferred to San Louis on the Senegal—The Frenchmen appropriate my schooner without condemnation—How they used her The sisters of charity in our prison—The trial scene in court, and our sentence—Friends attempt to facilitate my escape, but our plans detected—I am transferred to a guard-ship in the stream—New projects for my escape—A jolly party and the nick of time, but the captain spoils the sport | 280 |

| CHAP. XLIV.—I am sent to France in the frigate Flora—Sisters of charity—The prison of Brest—My prison companions—Prison mysteries—Corporal Blon—I apply to the Spanish minister—Transfer to the civil prison | 286 |

| CHAP. XLV.—Madame Sorret and my new quarters—Mode of life—A lot of Catalan girls—Prison boarding and lodging—Misery of the convicts in the coast prisons—Improvement of the central prisons | 292 |

| CHAP. XLVI.—New lodgers in our quarters—How we pass our time in pleasant diversions by aid of the Catalan girls and my cash—Soirées—My funds give out—Madame Sorret makes a suggestion—I turn schoolmaster, get pupils, teach English and penmanship, and support my whole party | 295 |

| CHAP. XLVII.—Monsieur Germaine, the forger—His trick—Cause of Germaine’s arrest—An adroit and rapid forgery—Its detection | 300 |

| CHAP. XLVIII.—Plan of escape—Germaine’s project against Babette—A new scheme for New Year’s night—Passports—Pietro Nazzolini and Dominico Antonetti—Preparations for our “French leave”—How the attempt eventuated | 304 |

| CHAP. XLIX.—Condition of the sentinel when he was found—His story—Prison researches next day—How we avoid detection—Louis Philippe receives my petition favorably—Germaine’s philosophic pilfering and principles—His plan to rob the Santissima Casa of Loretto—He designs making an attempt on the Emperor Nicholas—I am released and banished from France | 310 |

| CHAP. L.—I go to Portugal, and return in disguise to Marseilles, in order to embark for Africa—I resolve to continue a slaver—A Marseilles hotel during the cholera—Doctor Du Jean and Madame Duprez—Humors of the table d’hôte—Coquetry and flirtation—A phrenological denouement | 316 |

| CHAP. LI.—I reach Goree, and hasten to Sierra Leone, where I become a coast-pilot to Gallinas—Site of that celebrated factory—Don Pedro Blanco—His monopoly of the Vey country—Slave-trade and its territorial extent prior to the American Scheme of Colonization—Blanco’s arrangements, telegraphs, &c. at Gallinas—Appearance and mode of life—Blanco and the Lords’ prayer in Latin | 324 |

| [Pg xv] CHAP. LII.—Anecdotes of Blanco—Growth of slave-trade in the Vey country—Local wars—Amarar and Shiakar—Barbarities of the natives | 330 |

| CHAP. LIII.—I visit Liberia, and observe a new phase of negro development—I go to New Sestros, and establish trade—Trouble with Prince Freeman—The value of gunpowder physic | 335 |

| CHAP. LIV.—My establishment at New Sestros, and how I created the slave-trade in that region—The ordeal of Saucy-Wood—My mode of attacking a superstitious usage, and of saving the victims—The story of Barrah and his execution | 339 |

| CHAP. LV.—No river at New Sestros—Beach—Kroomen and Fishmen—Bushmen—Kroo boats—I engage a fleet of them for my factory—I ship a cargo of slaves in a hurry—My mode of operating—Value of rum and mock coral beads—Return of the cruiser | 344 |

| CHAP. LVI.—I go on a pleasure voyage in the Brilliant, accompanied by Governor Findley—Murder of the Governor—I fit out an expedition to revenge his death—A fight with the beach negroes—We burn five towns—A disastrous retreat—I am wounded—Vindication of Findley’s memory | 349 |

| CHAP. LVII.—What Don Pedro Blanco thought of my Quixotism—Painful effects of my wound—Blanco’s liberality to Findley’s family—My slave nurseries on the coast—Digby—I pack nineteen negroes on my launch, and set sail for home—Disastrous voyage—Stories—I land my cargo at night at Monrovia, and carry it through the colony!—Some new views of commercial Morality! | 356 |

| CHAP. LVIII.—My compliments to British cruisers—The Bonito—I offer an inspection of my barracoons, &c., to her officers—A lieutenant and the surgeon are sent ashore—My reception of them, and the review of my slaves, feeding, sleeping, &c.—Our night frolic—Next morning—A surprise—The Bonito off, and her officers ashore!—Almost a quarrel—How I pacified my guests over a good breakfast—Sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander | 362 |

| CHAP. LIX.—Ups and downs—I am captured in a Russian vessel, and sent to Sierra Leone—It is resolved that I am to be despatched to England—I determine to take French leave—Preparation to celebrate a birthday—A feast—A martinet—Corporal Blunt—Pleasant effects of cider—A swim for life and liberty at night—My concealment—I manage to equip myself, and depart in a Portuguese vessel—I ship thirty-one slaves at Digby—A narrow escape from a cruiser—My return to New Sestros—Report of my death—How I restored confidence in my actual existence—Don Pedro’s notion of me—The gift of a donkey, and its disastrous effect on the married ladies of New Sestros | 369 |

| CHAP. LX.—The confession of a dying sailor—Sanchez—The story of the murder of Don Miguel, and destruction of his factory by Thompson—A piratical revenge—An auto-da-fé at sea | 377 |

| CHAP. LXI.—My establishment at Digby—The rival kinsmen, and their quarrel—Jen-ken, the Bushman—My arrival at Digby, carousal—A night attack by the rival and his allies—A rout—Horrid scenes of massacre, barbarity, and cannibalism—My position and ransom | 382 |

| CHAP. LXII.—I escape from the bloody scene in a boot with a Krooman—Storm on the coast—My perilous attempt to land at Gallinas—How I am warned off—An African tornado—The sufferings of my companion and myself while exposed in the boat, and our final rescue | 387 |

| CHAP. LXIII.—Don Pedro Blanco leaves Gallinas—I visit Cape Mount, to restore his son to the Chief—His reception—I go to England in the Gil Blas; she is run [Pg xvi] down by steamer in the Channel—Rescued, and reach Dover—I see London and the British Islands—The diversions, sufferings, and opinions of my servant Lunes in Great Britain—He leaves voluntarily for Africa—A queer chat and scene with the ladies—His opinion of negro dress and negro bliss | 391 |

| CHAP. LXIV.—I make arrangements for future trade and business with Mr. Redman—I go to Havana, resolved to obtain a release from Blanco, and engage in lawful commerce—Don Pedro refuses, and sends me back with a freight—A voyage with two African females revisiting their native country—Their story in Cuba; results of frugality and industry—Shiakar’s daughter—Her reception at home—Her disgust with her savage home in Africa, and return to Cuba | 396 |

| CHAP. LXV.—I find my establishment in danger, from the colonists and others—A correspondence with Lieut. Bell, U. S. N.—Harmless termination of Governor Buchanan’s onslaught—Threatened with famine; my relief—The Volador takes 749 slaves;—The last cargo I ever shipped | 399 |

| CHAP. LXVI.—I am attacked by the British cruiser Termagant, Lieut. Seagram—Correspondence and diplomacy—I go on board the cruiser in a damp uniform—My reception and jollification—I confess my intention to abandon the Slave-trade—My compact with Seagram—How we manage Prince Freeman—His treaty with the Lieutenant for the suppression of the trade—The negro’s duplicity outwits himself—The British officer guaranties the safe removal of my property, whereupon I release 100 slaves—Captain Denman’s destruction of Gallinas—Freeman begins to see my diplomacy, and regrets his inability to plunder my property, as the natives had done at Gallinas—His plot to effect this—How I counteract it | 405 |

| CHAP. LXVII.—My barracoons destroyed—Adieus to New Sestros—I sail with Seagram, in the Termagant, for Cape Mount—A slaver in sight—All the nautical men depart to attack her in boats during a calm—I am left in charge of Her Britannic Majesty’s cruiser—The fruitless issue—Escape of the Serea | 411 |

| CHAP. LXVIII.—We land at Cape Mount, and obtain a cession of territory, by deed, from King Fana-Toro and Prince Gray—I explore the region—Site of old English slave factory—Difficulty of making the negroes comprehend my improvements at New Florence—Negro speculations and philosophy in regard to labor. | 414 |

| CHAP. LXIX.—Visit to Monrovia—Description of the colony and its products—Speculations on the future of the republic, and the character of colored colonization | 419 |

| CHAP. LXX.—I remove, and settle permanently at New Florence—I open communications with cruisers to supply them with provisions, &c.—Anecdote of Soma, the gambler—His sale and danger in the hands of a Bushman—Mode of gambling one’s self away in Africa—A letter from Governor Macdonald destroys my prospect of British protection—I haul down the British flag—I determine to devote myself to husbandry—Bad prospect | 424 |

| CHAP. LXXI.—Account of the character of the Vey negroes—The Gree-gree bush—Description of this institution, its rites, services, and uses—Marriage and midwifery—A scene with Fana-Toro, at Toso—Human sacrifice of his enemy; frying a heart; indignity committed on the body—Anecdote of the king’s endurance; burns his finger as a test, and rallies his men—Death of Prince Gray—Funeral rites among the Vey people—Smoking the corpse—I am offered the choice of his widows | 429 |

| CHAP. LXXII.—My workshops, gardens, and plantations at the Cape Mount settlement—I do not prosper as a farmer or trader with the interior—I decide to send [Pg xvii] a coaster to aid in the transfer of the Yankee clipper A—— to a slaver—I part on bad terms with the British—Game at Cape Mount—Adventure of a boy and an Ourang-outang—How we killed leopards, and saved our castle—Mode of hunting elephants—Elephant law | 437 |

| CHAP. LXXIII.—Fana-Toro’s war, and its effect on my establishment—I decline joining actively in the conflict—I allow captives to be shipped by a Gallinas factor—Two years of blockade by the British—A miraculous voyage of a long-boat with thirty-three slaves to Bahia—My disasters and mishaps at Cape Mount in consequence of this war—Exaggerations of my enemies—My true character—Letter from Rev. John Seys to me—My desire to aid the missionaries—Cain and Curtis stimulate the British against me—Adventure of the Chancellor—the British destroy my establishment—Death of Fana-Toro—The natives revenge my loss—The end | 442 |

Whilst Bonaparte was busy conquering Italy, my excellent father, Louis Canot, a captain and paymaster in the French army, thought fit to pursue his fortunes among the gentler sex of that fascinating country, and luckily won the heart and hand of a blooming Piedmontese, to whom I owe my birth in the capital of Tuscany.

My father was faithful to the Emperor as well as the Consul. He followed his sovereign in his disasters as well as glory: nor did he falter in allegiance until death closed his career on the field of Waterloo.

Soldiers’ wives are seldom rich, and my mother was no exception to the rule. She was left in very moderate circumstances, with six children to support; but the widow of an old campaigner, who had partaken the sufferings of many a long and dreary march with her husband, was neither disheartened by the calamity, nor at a loss for thrifty expedients to educate her younger offspring. Accordingly, I was kept at school, studying geography, arithmetic, history and the languages, until near twelve years old, when it was thought time for me to choose a profession. At school, and in my leisure hours, I had always [Pg 2] been a greedy devourer of books of travel, or historical narratives full of stirring incidents, so that when I avowed my preference for a sea-faring life, no one was surprised. Indeed, my fancy was rather applauded, as two of my mother’s brothers had served in the Neapolitan navy, under Murat. Proper inquiries were quickly made at Leghorn; and, in a few weeks, I found myself on the mole of that noble seaport, comfortably equipped, with a liberal outfit, ready to embark, as an apprentice, upon the American ship Galatea, of Boston.

It was in the year 1819, that I first saluted the element upon which it has been my destiny to pass so much of my life. The reader will readily imagine the discomforts to which I was subjected on this voyage. Born and bred in the interior of Italy, I had only the most romantic ideas of the sea. My opinions had been formed from the lives of men in loftier rank and under more interesting circumstances. My career was necessarily one of great hardship; and, to add to my misfortunes, I had neither companion nor language to vent my grief and demand sympathy. For the first three months, I was the butt of every joker in the ship. I was the scape-goat of every accident and of every one’s sins or carelessness. As I lived in the cabin, each plate, glass, or utensil that fell to leeward in a gale, was charged to my negligence. Indeed, no one seemed to compassionate my lot save a fat, lubberly negro cook, whom I could not endure. He was the first African my eye ever fell on, and I must confess that he was the only friend I possessed during my early adventures.

Besides the officers of the Galatea, there was a clerk on board, whom the captain directed to teach me English, so that, by the time we reached Sumatra, I was able to stand up for my rights, and plead my cause. As we could not obtain a cargo of pepper on the island, we proceeded to Bengal; and, on our arrival at Calcutta, the captain, who was also supercargo, took apartments on shore, where the clerk and myself were allowed to follow him.

According to the fashion of that period, the house provided for our accommodation was a spacious and elegant one, equipped with every oriental comfort and convenience, while fifteen or [Pg 3] twenty servants were always at the command of its inmates. For three months we lived like nabobs, and sorry, indeed, was I when the clerk announced that the vessel’s loading was completed, and our holiday over.

On the voyage home, I was promoted from the cabin, and sent into the steerage to do duty as a “light hand,” in the chief mate’s watch. Between this officer and the captain there was ill blood, and, as I was considered the master’s pet, I soon began to feel the bitterness of the subordinate’s spite. This fellow was not only cross-grained, but absolutely malignant. One day, while the ship was skimming along gayly with a five-knot breeze, he ordered me out to the end of the jib-boom to loosen the sail; yet, without waiting until I was clear of the jib, he suddenly commanded the men who were at the halliards to hoist the canvas aloft. A sailor who stood by pointed out my situation, but was cursed into silence. In a moment I was jerked into the air, and, after performing half a dozen involuntary summersets, was thrown into the water, some distance from the ship’s side. When I rose to the surface, I heard the prolonged cry of the anxious crew, all of whom rushed to the ship’s side, some with ropes’ ends, some with chicken coops, while others sprang to the stern boat to prepare it for launching. In the midst of the hurly-burly, the captain reached the deck, and laid the ship to; the sailor who had remonstrated with the mate having, in the meantime, clutched that officer, and attempted to throw him over, believing I had been drowned by his cruelty. As the sails of the Galatea flattened against the wind, many an anxious eye was strained over the water in search of me; but I was nowhere seen! In truth, as the vessel turned on her heel, the movement brought her so close to the spot where I rose, that I clutched a rope thrown over for my rescue, and climbed to the lee channels without being perceived. As I leaped to the deck, I found one half the men in tumultuous assemblage around the struggling mate and sailor; but my sudden apparition served to divert the mob from its fell purpose, and, in a few moments, order was perfectly restored. Our captain was an intelligent and just man, as may be readily supposed from the fact that he exclusively [Pg 4] controlled so valuable an enterprise. Accordingly, the matter was examined with much deliberation; and, on the following day, the chief mate was deprived of his command. I should not forget to mention that, in the midst of the excitement, my sable friend the cook leaped overboard to rescue his protegé. Nobody happened to notice the darkey when he sprang into the sea; and, as he swam in a direction quite contrary from the spot where I fell, he was nigh being lost, when the ship’s sails were trimmed upon her course. Just at that moment a faint call was heard from the sea, and the woolly skull perceived in time for rescue.

This adventure elevated not only “little Theodore,” but our “culinary artist” in the good opinion of the mess. Every Saturday night my African friend was allowed to share the cheer of the forecastle, while our captain presented him with a certificate of his meritorious deed, and made the paper more palatable by the promise of a liberal bounty in current coin at the end of the voyage.

I now began to feel at ease, and acquire a genuine fondness for sea life. My aptitude for languages not only familiarized me with English, but enabled me soon to begin the scientific study of navigation, in which, I am glad to say, that Captain Solomon Towne was always pleased to aid my industrious efforts.

We touched at St. Helena for supplies, but as Napoleon was still alive, a British frigate met us within five miles of that rock-bound coast, and after furnishing a scant supply of water, bade us take our way homeward.

I remember very well that it was a fine night in July, 1820, when we touched the wharf at Boston, Massachusetts. Captain Towne’s family resided in Salem, and, of course, he was soon on his way thither. The new mate had a young wife in Boston, and he, too, was speedily missing. One by one, the crew sneaked off in the darkness. The second mate quickly found an excuse for a visit in the neighborhood; so that, by midnight, the Galatea, with a cargo valued at about one hundred and twenty thousand dollars, was intrusted to the watchfulness of a stripling cabin-boy.

I do not say it boastfully, but it is true that, whenever I [Pg 5] have been placed in responsible situations, from the earliest period of my recollection, I felt an immediate stirring of that pride which always made me equal, or at least willing, for the required duty. All night long I paced the deck. Of all the wandering crowd that had accompanied me nearly a year across many seas, I alone had no companions, friends, home, or sweetheart, to seduce me from my craft; and I confess that the sentiment of loneliness, which, under other circumstances, might have unmanned me at my American greeting, was stifled by the mingled vanity and pride with which I trod the quarter-deck as temporary captain.

When dawn ripened into daylight, I remembered the stirring account my shipmates had given of the beauty of Boston, and I suddenly felt disposed to imitate the example of my fellow-sailors. Honor, however, checked my feet as they moved towards the ship’s ladder; so that, instead of descending her side, I closed the cabin door, and climbed to the main-royal yard, to see the city at least, if I could not mingle with its inhabitants. I expected to behold a second Calcutta; but my fancy was not gratified. Instead of observing the long, glittering lines of palaces and villas I left in India and on the Tuscan shore, my Italian eyes were first of all saluted by dingy bricks and painted boards. But, as my sight wandered away from the town, and swept down both sides of the beautiful bay, filled with its lovely islands, and dressed in the fresh greenness of summer, I confess that my memory and heart were magically carried away into the heart of Italy, playing sad tricks with my sense of duty, when I was abruptly restored to consciousness by hearing the heavy footfall of a stranger on deck.

The intruder—as well as I could see from aloft—seemed to be a stout, elderly person. I did not delay to descend the ratlins, but slid down a back-stay, just in time to meet the stranger as he approached our cabin. My notions of Italian manners did not yet permit me to appreciate the greater freedom and social liberty with which I have since become so familiar in America, and it may naturally be supposed that I was rather peremptory in ordering the inquisitive Bostonian to leave the [Pg 6] ship. I was in command—in my first command; and so unceremonious a visit was peculiarly annoying. Nor did the conduct of the intruder lessen my anger, as, quietly smiling at my order, he continued moving around the ship, and peered into every nook and corner. Presently he demanded whether I was alone? My self-possession was quite sufficient to leave the question unanswered; but I ordered him off again, and, to enforce my command, called a dog that did not exist. My ruse, however, did not succeed. The Yankee still continued his examination, while I followed closely on his heels, now and then twitching the long skirts of his surtout to enforce my mandate for his departure.

During this promenade, my unwelcome guest questioned me about the captain’s health,—about the mate,—as to the cause of his dismissal,—about our cargo,—and the length of our voyage. Each new question begot a shorter and more surly answer. I was perfectly satisfied that he was not only a rogue, but a most impudent one; and my Franco-Italian temper strained almost to bursting.

By this time, we approached the house which covered the steering-gear at the ship’s stern, and in which were buckets containing a dozen small turtles, purchased at the island of Ascension, where we stopped to water after the refusal at St. Helena. The turtle at once attracted the stranger’s notice, and he promptly offered to purchase them. I stated that only half the lot belonged to me, but that I would sell the whole, provided he was able to pay. In a moment, my persecutor drew forth a well-worn pocket-book, and handing me six dollars, asked whether I was satisfied with the price. The dollars were unquestionable gleams, if not absolute proofs, of honesty, and I am sure my heart would have melted had not the purchaser insisted on taking one of the buckets to convey the turtles home. Now, as these charming implements were part of the ship’s pride, as well as property, and had been laboriously adorned by our marine artists with a spread eagle and the vessel’s name, I resisted the demand, offering, at the same time, to return the money. But my turtle-dealer was not to be repulsed so easily; his ugly smile still sneered in my face as he endeavored to push me aside and drag [Pg 7] the bucket from my hand. I soon found that he was the stronger of the two, and that it would be impossible for me to rescue my bucket fairly; so, giving it a sudden twist and shake, I contrived to upset both water and turtles on the deck, thus sprinkling the feet and coat-tails of the veteran with a copious ablution. To my surprise, however, the tormentor’s cursed grin not only continued but absolutely expanded to an immoderate laugh, the uproariousness of which was increased by another suspicious Bostonian, who leaped on deck during our dispute. By this time I was in a red heat. My lips were white, my checks in a blaze, and my eyes sparks. Beyond myself with ferocious rage, I gnashed my teeth, and buried them in the hand which I could not otherwise release from its grasp on the bucket. In the scramble, I either lost or destroyed part of my bank notes; yet, being conqueror at last, I became clement, and taking up my turtles, once more insisted upon the departure of my annoyers. There is no doubt that I larded my language with certain epithets, very current among sailors, most of which are learned more rapidly by foreigners than the politer parts of speech.

Still the abominable monster, nothing daunted by my onslaught, rushed to the cabin, and would doubtless have descended, had not I been nimbler than he in reaching the doors, against which I placed my back, in defiance. Here, of course, another battle ensued, enlivened by a chorus of laughter from a crowd of laborers on the wharf. This time I could not bite, yet I kept the apparent thief at bay with my feet, kicking his shins unmercifully whenever he approached, and swearing in the choicest Tuscan.

He who knows any thing of Italian character, especially when it is additionally spiced by French condiments, may imagine the intense rage to which so volcanic a nature as mine was, by this time, fully aroused. Language and motion were nearly exhausted. I could neither speak nor strike. The mind’s passion had almost produced the body’s paralysis. Tears began to fall from my eyes: but still he laughed! At length, I suddenly flung wide the cabin doors, and leaping below at a bound, seized from the rack a loaded musket, with which I rushed upon deck. As soon [Pg 8] as the muzzle appeared above the hatchway, my tormentor sprang over the ship, and by the time I reached the ladder, I found him on the wharf, surrounded by a laughing and shouting crowd. I shook my head menacingly at the group; and shouldering my firelock, mounted guard at the gangway. It was fully a quarter of an hour that I paraded (occasionally ramming home my musket’s charge, and varying the amusement by an Italian defiance to the jesters), before the tardy mate made his appearance on the wharf. But what was my consternation, when I beheld him advance deferentially to my pestilent visitor, and taking off his hat, respectfully offer to conduct him on board! This was a great lesson to me in life on the subject of “appearances.” The shabby old individual was no less a personage than the celebrated William Gray, of Boston, owner of the Galatea and cargo, and proprietor of many a richer craft then floating on every sea.

But Mr. Gray was a forgiving enemy. As he left the ship that morning, he presented me fifty dollars, “in exchange,” he said, “for the six destroyed in protection of his property;” and, on the day of my discharge, he not only paid the wages of my voyage, but added fifty dollars more to aid my schooling in scientific navigation.

Four years after, I again met this distinguished merchant at the Marlborough Hotel, in Boston. I was accompanied, on that occasion, by an uncle who visited the United States on a commercial tour. When my relative mentioned my name to Mr. Gray, that gentleman immediately recollected me, and told my venerable kinsman that he never received such abuse as I bestowed on him in July, 1820! The sting of my teeth, he declared, still tingled in his hand, while the kicks I bestowed on his ankles, occasionally displayed the scars they had left on his limbs. He seemed particularly annoyed, however, by some caustic remarks I had made about his protuberant stomach, and forgave the blows but not the language.

My uncle, who was somewhat of a tart disciplinarian, gave me an extremely black look, while, in French, he demanded an explanation of my conduct. I knew Mr. Gray, however, better than my relative; and so, without heeding his reprimand, I [Pg 9] answered, in English, that if I cursed the ship’s owner on that occasion, it was my debut in the English language on the American continent; and as my Anglo-Saxon education had been finished in a forecastle, it was not to be expected I should be select in my vocabulary. “Never the less,” I added, “Mr. Gray was so delighted with my accolade, that he valued my defence of his property and our delicious tête-à-tête at the sum of a hundred dollars!”

The anecdote told in the last chapter revived my uncle’s recollection of several instances of my early impetuosity; among which was a rencounter with Lord Byron, while that poet was residing at his villa on the slope of Monte Negro near Leghorn, which he took the liberty to narrate to Mr. Gray.

A commercial house at that port, in which my uncle had some interest, was the noble lord’s banker;—and, one day, while my relative and the poet were inspecting some boxes recently arrived from Greece, I was dispatched to see them safely deposited in the warehouse. Suddenly, Lord Byron demanded a pencil. My uncle had none with him, but remembering that I had lately been presented one in a handsome silver case, requested the loan of it. Now, as this was my first silver possession, I was somewhat reluctant to let it leave my possession even for a moment, and handed it to his lordship with a bad grace. When the poet had made his memorandum, he paused a moment, as if lost in thought, and then very unceremoniously—but, doubtless, in a fit of abstraction—put the pencil in his pocket. If I had already visited America at that time, it is likely that I would have warned the Englishman of his mistake on the spot; but, as children in the Old World are rather more curbed in their intercourse with elders than on this side of the Atlantic, I bore the forgetfulness as well as I could until next morning. Summoning all my resolution, I repaired without my uncle’s knowledge to the poet’s house at an early hour, and after much difficulty was [Pg 11] admitted to his room. He was still in bed. Every body has heard of Byron’s peevishness, when disturbed or intruded on. He demanded my business in a petulant and offensive tone. I replied, respectfully, that on the preceding day I loaned him a silver pencil,—strongly emphasizing and repeating the word silver,—which, I was grieved to say, he forgot to return. Byron reflected a moment, and then declared he had restored it to me on the spot! I mildly but firmly denied the fact; while his lordship as sturdily reasserted it. In a short time, we were both in such a passion that Byron commanded me to leave the room. I edged out of the apartment with the slow, defying air of angry boyhood; but when I reached the door, I suddenly turned, and looking at him with all the bitterness I felt for his nation, called him, in French, “an English hog!” Till then our quarrel had been waged in Italian. Hardly were the words out of my mouth when his lordship leaped from the bed, and in the scantiest drapery imaginable, seized me by the collar, inflicting such a shaking as I would willingly have exchanged for a tertian ague from the Pontine marshes. The sudden air-bath probably cooled his choler, for, in a few moments, we found ourselves in a pacific explanation about the luckless pencil. Hitherto I had not mentioned my uncle; but the moment I stated the relationship, Byron became pacified and credited my story. After searching his pockets once more ineffectually for the lost silver, he presented me his own gold pencil instead, and requested me to say why I “cursed him in French?”

“My father was a Frenchman, my lord,” said I.

“And your mother?”

“She is an Italian, sir.”

“Ah! no wonder, then, you called me an ‘English hog.’ The hatred runs in the blood; you could not help it.”

After a moment’s hesitation, he continued,—still pacing the apartment in his night linen,—“You don’t like the English, do you, my boy?”

“No,” said I, “I don’t.”

“Why?” returned Byron, quietly.

“Because my father died fighting them,” replied I.

[Pg 12] “Then, youngster, you have a right to hate them,” said the poet, as he put me gently out of the door, and locked it on the inside.

A week after, one of the porters of my uncle’s warehouse offered to sell, at an exorbitant price, what he called “Lord Byron’s pencil,” declaring that his lordship had presented it to him. My uncle was on the eve of bargaining with the man, when he perceived his own initials on the silver. In fact, it was my lost gift. Byron, in his abstraction, had evidently mistaken the porter for myself; so the servant was rewarded with a trifling gratuity, while my virtuoso uncle took the liberty to appropriate the golden relic of Byron to himself, and put me off with the humbler remembrance of his honored name.

These, however, are episodes. Let us return once more to the Galatea and her worthy commander.

Captain Towne retired to Salem after the hands were discharged, and took me with him to reside in his family until he was ready for another voyage. In looking back through the vista of a stormy and adventurous life, my memory lights on no happier days than those spent in this sea-faring emporium. Salem, in 1821, was my paradise. I received more kindness, enjoyed more juvenile pleasures, and found more affectionate hospitality in that comfortable city than I can well describe. Every boy was my friend. No one laughed at my broken English, but on the contrary, all seemed charmed by my foreign accent. People thought proper to surround me with a sort of romantic mystery, for, perhaps, there was a flavor of the dashing dare-devil in my demeanor, which imparted influence over homelier companions. Besides this, I soon got the reputation of a scholar. I was considered a marvel in languages, inasmuch as I spoke French, Italian, Spanish, English, and professed a familiarity with Latin. I remember there was a wag in Salem, who, determining one day to test my acquaintance with the latter tongue, took me into a neighboring druggist’s, where there were some Latin volumes, and handed me one with the request to translate a page, either verbally or on paper. Fortunately, the book he produced was Æsop, whose fables had been so thoroughly studied by me two [Pg 13] years before, that I even knew some of them by heart. Still, as I was not very well versed in the niceties of English, I thought it prudent to make my version of the selected fable in French; and, as there was a neighbor who knew the latter language perfectly, my translation was soon rendered into English, and the proficiency of the “Italian boy” conceded.

I sailed during five years from Salem on voyages to various parts of the world, always employing my leisure, while on shore and at sea, in familiarizing myself minutely with the practical and scientific details of the profession to which I designed devoting my life. I do not mean to narrate the adventures of those early voyages, but I cannot help setting down a single anecdote of that fresh and earnest period, in order to illustrate the changes that time and “circumstances” are said to work on human character.

In my second voyage to India, I was once on shore with the captain at Quallahbattoo, in search of pepper, when a large proa, or Malay canoe, arrived at the landing crammed with prisoners, from one of the islands. The unfortunate victims were to be sold as slaves. They were the first slaves I had seen! As the human cargo was disembarked, I observed one of the Malays dragging a handsome young female by the hair along the beach. Cramped by long confinement in the wet bottom of the canoe, the shrieking girl was unable to stand or walk. My blood was up quickly. I ordered the brute to desist from his cruelty; and, as he answered with a derisive laugh, I felled him to the earth with a single blow of my boat-hook. This impetuous vindication of humanity forced us to quit Quallahbattoo in great haste; but, at the age of seventeen, my feelings in regard to slavery were very different from what this narrative may disclose them to have become in later days.

When my apprenticeship was over, I made two or three successful voyages as mate, until—I am ashamed to say,—that a “disappointment” caused me to forsake my employers, and to yield to the temptations of reckless adventure. This sad and early blight overtook me at Antwerp,—a port rather noted for [Pg 14] the backslidings of young seamen. My hard-earned pay soon diminished very sensibly, while I was desperately in love with a Belgian beauty, who made a complete fool of me—for at least three months! From Antwerp, I betook myself to Paris to vent my second “disappointment.” The pleasant capital of la belle France was a cup that I drained at a single draught. Few young men of eighteen or twenty have lived faster. The gaming tables at Frascati’s and the Palais Royal finished my consumptive purse; and, leaving an empty trunk as a recompense for my landlord, I took “French leave” one fine morning, and hastened to sea.

The reader will do me the justice to believe that nothing but the direst necessity compelled me to embark on board a British vessel, bound to Brazil. The captain and his wife who accompanied him, were both stout, handsome Irish people, of equal age, but addicted to fondness for strong and flavored drinks.

My introduction on board was signalized by the ceremonious bestowal upon me of the key of the spirit-locker, with a strict injunction from the commander to deny more than three glasses daily either to his wife or himself. I hardly comprehended this singular order at first, but, in a few days, I became aware of its propriety. About eleven o’clock her ladyship generally approached when I was serving out the men’s ration of gin, and requested me to fill her tumbler. Of course, I gallantly complied. When I returned from deck below with the bottle, she again required a similar dose, which, with some reluctance, I furnished. At dinner the dame drank porter, but passed off the gin on her credulous husband as water. This system of deception continued as long as the malt liquor lasted, so that her ladyship received and swallowed daily a triple allowance of capital grog. Indeed, it is quite astonishing what quantities of the article can sometimes be swallowed by sea-faring women. The oddness of their appetite for the cordials is not a little enhanced by the well-known aversion the sex have to spirituous fluids, in every shape, on shore. Perhaps the salt air may have something to do with the acquired relish; but, as I am not composing an [Pg 15] essay on temperance, I shall leave the discussion to wiser physiologists.

My companions’ indulgence illustrated another diversity between the sexes, which I believe is historically true from the earliest records to the present day. The lady broke her rule, but the captain adhered faithfully to his. Whilst on duty, the allotted three glasses completed his potations. But when we reached Rio de Janeiro, and there was no longer need of abstinence, save for the sake of propriety, both my shipmates gave loose to their thirst and tempers. They drank, quarrelled, and kissed, with more frequency and fervor than any creatures it has been my lot to encounter throughout an adventurous life. After we got the vessel into the inner harbor,—though not without a mishap, owing to the captain’s drunken stubbornness,—my Irish friends resolved to take lodgings for a while on shore. For two days they did not make their appearance; but toward the close of the third, they returned, “fresh,” as they said, “from the theatre.” It was very evident that the jolly god had been their companion; and, as I was not a little scandalized by the conjugal scenes which usually closed these frolics, I hastened to order tea under the awning on deck, while I betook myself to a hammock which was slung on the main boom. Just as I fell off into pleasant dreams, I was roused from my nap by a prelude to the opera. Madame gave her lord the lie direct. A loaf of bread, discharged against her head across the table, was his reply. Not content with this harmless demonstration of rage, he seized the four corners of the table-cloth, and gathering the tea-things and food in the sack, threw the whole overboard into the bay. In a flash, the tigress fastened on his scanty locks with one hand, while, with the other, she pummelled his eyes and nose. Badly used as he was, I must confess that the captain proved too generous to retaliate on that portion of his spouse where female charms are most bewitching and visible; still, I am much mistaken if the sound spanking she received did not elsewhere leave marks of physical vigor that would have been creditable to a pugilist.

It was remarkable that these human tornados were as violent [Pg 16] and brief as those which scourge tropical lands as well as tropical characters. In a quarter of an hour there was a dead calm. The silence of the night, on those still and star-lit waters, was only broken by a sort of chirrup, that might have been mistaken for a cricket, but which I think was a kiss. Indeed, I was rapidly going off again to sleep, when I was called to give the key of the spirit-locker,—a glorious resource that never failed as a solemn seal of reconciliation and bliss.

Next morning, before I awoke, the captain went ashore, and when his wife, at breakfast, inquired my knowledge of the night’s affray, my gallantry forced me to confess that I was one of the soundest sleepers on earth or water, and, moreover, that I was surprised to learn there had been the least difference between such happy partners. In spite of my simplicity, the lady insisted on confiding her griefs, with the assurance that she would not have been half so angry had not her spouse foolishly thrown her silver spoons into the sea, with the bread and butter. She grew quite eloquent on the pleasures of married life, and told me of many a similar reproof she had been forced to give her husband during their voyages. It did him good, she said, and kept him wholesome. In fact, she hoped, that if ever I married, I would have the luck to win a guardian like herself. Of course, I was again most gallantly silent. Still, I could not help reserving a decision as to the merits of matrimony; for present appearances certainly did not demonstrate the bliss I had so often read and heard of. At any rate, I resolved, that if ever I ventured upon a trial of love, it should, at least, in the first instance, be love without liquor!

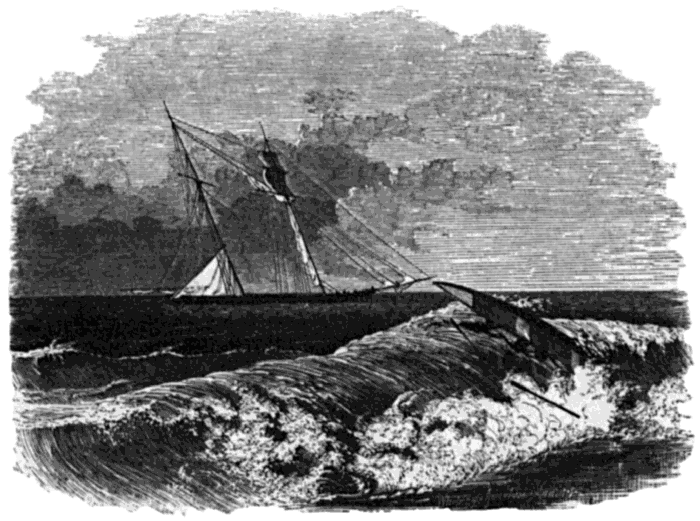

On our return to Europe we called at Dover for orders, and found that Antwerp was our destination. We made sail at sunset, but as the wind was adverse and the weather boisterous, we anchored for two days in the Downs. At length, during a lull of the gale, we sailed for the mouth of the Scheldt; but, as we approached the coast of Holland, the wind became light and baffling, so that we were unable to enter the river. We had not taken a pilot at Ramsgate, being confident of obtaining one off Flushing. At sundown, the storm again arose in all its fury [Pg 17] from the north-west; but all attempts to put back to England were unavailing, for we dared not show a rag of sail before the howling tempest. It was, indeed, a fearful night of wind, hail, darkness, and anxiety. At two o’clock in the morning, we suddenly grounded on one of the numerous banks off Flushing. Hardly had we struck when the sea made a clean sweep over us, covering the decks with sand, and snapping the spars like pipe-stems. The captain was killed instantly by the fall of a top-gallant yard, which crushed his skull; while the sailors, who in such moments seem possessed by utter recklessness, broke into the spirit-room and drank to excess. For awhile I had some hope that the stanchness of our vessel’s hull might enable us to cling to her till daylight, but she speedily bilged and began to fill.

After this it would have been madness to linger. The boats were still safe. The long one was quickly filled by the crew, under the command of the second mate—who threw an anker of gin into the craft before he leaped aboard,—while I reserved the jolly-boat for myself, the captain’s widow, the cook, and the steward. The long-boat was never heard of.

All night long that dreadful nor’wester howled along and lashed the narrow sea between England and the Continent; yet I kept our frail skiff before it, hoping, at daylight, to descry the lowlands of Belgium. The heart-broken woman rested motionless in the stern-sheets. We covered her with all the available garments, and, even in the midst of our own griefs, could not help feeling that the suddenness of her double desolation had made her perfectly unconscious of our dreary surroundings.

Shortly after eight o’clock a cry of joy announced the sight of land within a short distance. The villagers of Bragden, who soon descried us, hastened to the beach, and rushing knee deep into the water, signalled that the shore was safe after passing the surf. The sea was churned by the storm into a perfect foam. Breakers roared, gathered, and poured along like avalanches. Still, there was no hope for us but in passing the line of these angry sentinels. Accordingly, I watched the swell, and pulling firmly, bow on, into the first of the breakers, we spun with such arrowy swiftness across the intervening space, that I recollect [Pg 18] nothing until we were clasped in the arms of the brawny Belgians on the beach.

But, alas! the poor widow was no more. I cannot imagine when she died. During the four hours of our passage from the wreck to land, her head rested on my lap; yet no spasm of pain or convulsion marked the moment of her departure.

That night the parish priest buried the unfortunate lady, and afterwards carried round a plate, asking alms,—not for masses to insure the repose of her soul,—but to defray the expenses of the living to Ostend.

I had no time or temper to be idle. In a week, I was on board a Dutch galliot, bound to Havana; but I soon perceived that I was again under the command of two captains—male and female. The regular master superintended the navigation, while the bloomer controlled the whole of us. Indeed, the dame was the actual owner of the craft, and, from skipper to cabin-boy, governed not only our actions but our stomachs. I know not whether it was piety or economy that swayed her soul, but I never met a person who was so rigid as this lady in the observance of the church calendar, especially whenever a day of abstinence allowed her to deprive us of our beef. Nothing but my destitution compelled me to ship in this craft; still, to say the truth, I had well-nigh given up all idea of returning to the United States, and determined to engage in any adventurous expedition that my profession offered. In 1824, it will be remembered, Mexico, the Spanish main, Peru, and the Pacific coasts, were renowned for the fortunes they bestowed on enterprise; and, as the galliot was bound to Havana, I hailed her as a sort of floating bridge to my El Dorado.

On the seventh night after our departure, while beating out of the bay of Biscay with a six-knot breeze, in a clear moonlight, we ran foul of a vessel which approached us on the opposite tack. Whence she sprang no one could tell. In an instant, she appeared [Pg 20] and was on us with a dreadful concussion. Every man was prostrated on deck and all our masts were carried away. From the other vessel we heard shrieks and a cry of despair; but the ill-omened miscreant disappeared as rapidly as she approached, and left us floating a helpless log, on a sea proverbial for storms.

We contrived, however, to reach the port of Ferrol, in Spain, where we were detained four months, in consequence of the difficulty of obtaining the materials for repairs, notwithstanding this place is considered the best and largest ship-yard of Castile.

It was at Ferrol that I met with a singular adventure, which was well-nigh depriving me of my personal identity, as Peter Schlemhil was deprived of his shadow. I went one afternoon in my boat to the other side of the harbor to obtain some pieces of leather from a tannery, and, having completed my purchase, was lounging slowly towards the quay, when I stopped at a house for a drink of water. I was handed a tumbler by the trim-built, black-eyed girl, who stood in the doorway, and whose rosy lips and sparkling eyes were more the sources of my thirst than the water; but, while I was drinking, the damsel ran into the dwelling, and hastily returned with her mother and another sister, who stared at me a moment without saying a word, and simultaneously fell upon my neck, smothering my lips and cheeks with repeated kisses!

“Oh! mi querido hijo,” said the mother.

“Carissimo Antonio,” sobbed the daughter.

“Mi hermano!” exclaimed her sister.

“Dear son, dear Antonio, dear brother! Come into the house; where have you been? Your grandmother is dying to see you once more! Don’t delay an instant, but come in without a word! Por dios! that we should have caught you at last, and in such a way: Ave Maria! madrecita, aqui viene Antonito!”

In the midst of all these exclamations, embraces, fondlings, and kisses, it may easily be imagined that I stood staring about me with wide eyes and mouth, and half-drained tumbler in hand, like one in a dream. I asked no questions, but as the dame was buxom, and the girls were fresh, I kissed in return, and followed [Pg 21] unreluctantly as they half dragged, half carried me into their domicil. On the door-sill of the inner apartment I found myself locked in the skinny arms of a brown and withered crone, who was said to be my grandmother, and, of course, my youthful moustache was properly bedewed with the moisture of her toothless mouth.

As soon as I was seated, I took the liberty to say,—though without any protest against this charming assault,—that I fancied there might possibly be some mistake; but I was quickly silenced. My madrecita declared at once, and in the presence of my four shipmates, that, six years before, I left her on my first voyage in a Dutch vessel; that my querido padre, had gone to bliss two years after my departure; and, accordingly, that now, I, Antonio Gomez y Carrasco, was the only surviving male of the family, and, of course, would never more quit either her, my darling sisters, or the old pobrecita, our grandmother. This florid explanation was immediately closed like the pleasant air of an opera by a new chorus of kisses, nor can there be any doubt that I responded to the embraces of my sweet hermanas with the most gratifying fraternity.

Our charming quartette lasted in all its harmony for half an hour, during which volley after volley of family secrets was discharged into my eager ears. So rapid was the talk, and so quickly was its thread taken up and spun out by each of the three, that I had no opportunity to interpose. At length, however, in a momentary lull and in a jocular manner,—but in rather bad Spanish,—I ventured to ask my loving and talkative mamma, “what amount of property my worthy father had deemed proper to leave on earth for his son when he took his departure to rest con Dios?” I thought it possible that this agreeable drama was a Spanish joke, got up al’ improvista, and that I might end it by exploding the dangerous mine of money: besides this, it was growing late, and my return to the galliot was imperative.

But alas! my question brought tears in an instant into my mother’s eyes, and I saw that the scene was not a jest. Accordingly, I hastened, in all seriousness, to explain and insist on their error. [Pg 22] I protested with all the force of my Franco-Italian nature and Spanish rhetoric, against the assumed relationship. But all was unavailing; they argued and persisted; they brought in the neighbors; lots of old women and old men, with rusty cloaks or shawls, with cigars or cigarillos in mouth, formed a jury of inquest; so that, in the end, there was an unanimous verdict in favor of my Galician nativity!

Finding matters had indeed taken so serious a turn, and knowing the impossibility of eradicating an impression from the female mind when it becomes imbedded with go much apparent conviction, I resolved to yield; and, assuming the manner of a penitent prodigal, I kissed the girls, embraced my mother, passed my head over both shoulders of my grand-dame, and promised my progenitors a visit next day.

As I did not keep my word, and two suns descended without my return, the imaginary “mother” applied to the ministers of law to enforce her rights over the truant boy. The Alcalde, after hearing my story, dismissed the claim; but my dissatisfied relatives summoned me, on appeal, before the governor of the district, nor was it without infinite difficulty that I at last succeeded in shaking off their annoying consanguinity.